The Weightless Magic of Coffee’s Aroma

How a little bean and some heat create the best smell in the world.

I can’t count the number of people who have told me: “I don’t drink coffee, but I love the smell of it.” There is no question that roasted coffee has an especially compelling, complex, and downright beautiful aroma. The coffee commercials of my childhood featured people smelling coffee more than drinking it. Every ad seemed to go the same way: a woman in a kitchen opened a can of coffee, filling the kitchen (and her life) with the enticing smell of home-brewed goodness. The commercials were loaded with images of people inhaling deeply the fragrance of a freshly opened can or a steaming cup of coffee and smiling blissfully. My favorite coffee commercial went: “No need to feel so blue, the aroma’s calling yoooouuu….”

We’ve talked about the chemical origin of coffee’s aromas before: they mainly come from Maillard reactions when coffee is roasted. Compounds that are stored in the seed of the coffee fruit while the coffee plant is growing are transformed by the heat of the roaster into thousands of chemicals. But how do those chemicals get to your nose? The key is the subject I wrote about a week ago: volatility.

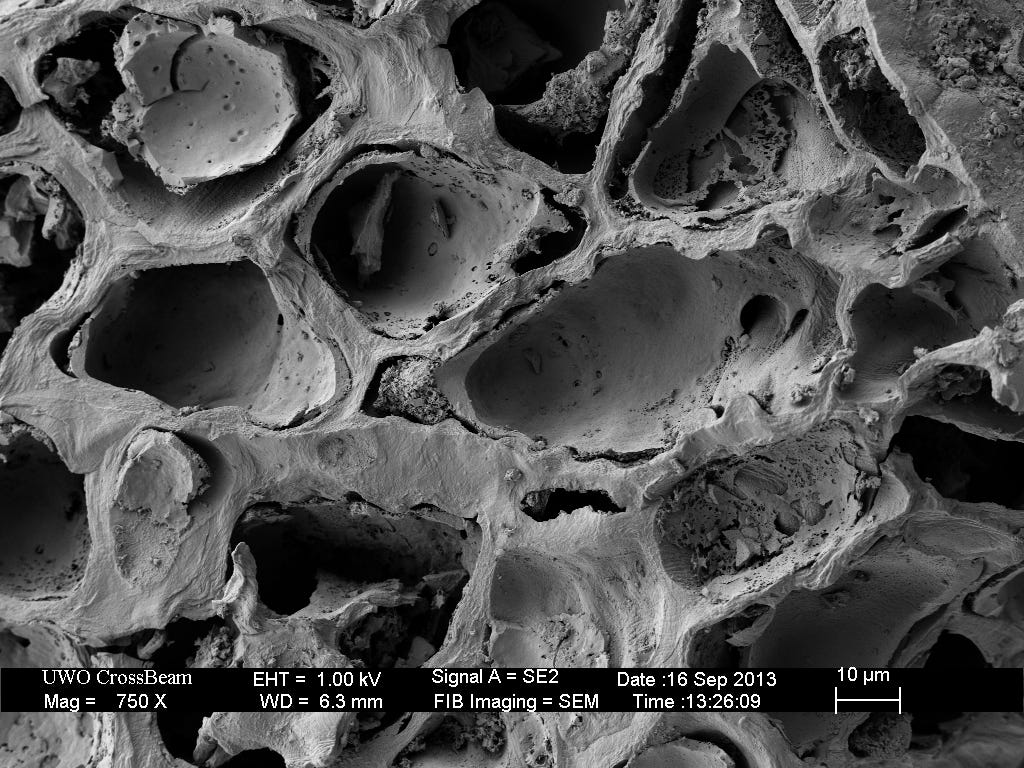

Here’s what happens in coffee’s case. The coffee seed (we call it a bean) is a tough little bugger, rich in lignin- which is the same thing that makes wood strong and durable. As coffee is roasted, water vapor is created from moisture in the bean, which creates pressure inside the cell walls of the coffee. The cells swell up like balloons, but the lignin fights back, resisting the steam pressure from inside the coffee. Eventually, the bean structure gives way, and the coffee bean emits a popping sound. Coffee roasters call this sound “first crack”, and it signifies the beginning of the browning stage of coffee roasting. The water vapor now gone, a new set of chemical reactions begins, called browning reactions. These reactions don’t give off water vapor, but they create another gas: carbon dioxide (CO2). The CO2 starts to puff up the cells in the same way the water vapor did, swelling the coffee cells even more. Over the course of a roast, the coffee about doubles in size from all the gas in its cells. Besides CO2, the cells contain thousands of oils, terpenes, acids, pyrazines, esters, and other chemicals, many of which are light and volatile. By the end of the roast, a coffee bean viewed through a microscope resembles a sponge, with a lattice of little chambers. These chambers are the inflated cells of the coffee seed- the walls of lignin holding in all the carbon dioxide and aromas produced during roasting.

Immediately after roasting, coffee begins to shed the CO2 produced during roasting, a process roasters call “outgassing”. But here’s what’s cool: though CO2 itself is odorless, the gas carries coffee aromatics along with it, providing a conduit for the aromatics to get into the air and into your nose. This is why coffee beans smell so powerful- their natural aroma is propelled by the CO2 gas inside its cells out into the world.

But lignin is very strong, and most of those cells remain intact, with the gas locked inside. And this is why, if we want to release the full aroma of a coffee bean, we must grind it. Grinding cuts the bean into thousands of tiny pieces, ripping apart the lignin structure, opening each one of the coffee’s cells and exposing it to air. The gases are been released, and the CO2 carries all those beautiful aromas into the sky. Fly, little aromas, fly! This is why grinding coffee just before brewing is so effective at maximizing coffee’s smell- the gases don’t have much time to dissipate, and can be dissolved into hot water during brewing.

Brewing coffee is therefore about dissolving volatile aromatics into water along with some tastes. And, since aromas, when accompanied by taste, create the perception we call “flavor”, these volatiles are a key part of coffee’s ultimate flavor profile. Aroma+taste=flavor. But hot coffee can barely hold on to some of those aromatics- they jump aboard the steam that rises from your cup, and create the delicious smell of a hot cup of coffee (see the glorious pictures from 70s coffee commercials above) This is also why cold coffee smells less intense than hot coffee does. But regardless of the temperature of the coffee when it’s sipped, it gets closer to body temperature in the mouth. By the time it’s swallowed, warm coffee vapors rise up the nasopharynx into the nasal cavity, where the aromatics can be smelled. Aroma+taste=flavor, remember?

This explains why the Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel is so named. Many of the attributes are primarily aromatic, but they become a part of flavor when the coffee is consumed. For this reason, almost all coffee flavors can be smelled. Floral, fruity, chocolate, brown sugar, spices…. it’s all there in those beautiful aromas that soar from the cup into the air. We train as coffee “tasters” by smelling aromatic references, because it’s largely smells that create the flavor of coffee in the first place. If you look at the categories in the center of the wheel- floral, fruity, sour/fermented, green/vegetative, roasted, spices, nutty/cocoa, and sweet, along with the precise descriptors as you move outward, you’ll realize that they are mostly aromatic descriptors. Coffee tastes sweet, sour, and bitter, but it smells like a million other things! And each of these aromas represent a little molecule that was light enough to hitch a ride on carbon dioxide or water vapor and get in to your nose. Magical.

Wonderful!