Recently, in a Facebook group, a person asked the question:

“Why does outside SMELL different during the day? I'm not talking about stuff my neighbors are doing (cooking, burning stuff, driving cars). I'm talking about a different SCENT outdoors that's like, maybe... Mineral-y (but not petrichor bc it's not raining)? "Fresh"? But also more than that? Like sometimes if my partner opens the sliding glass door while I'm still in bed, I can "smell" morning before I even see it (I sleep with eye mask).”

It's a good question and it gets to the secret that underlies all of smell. And that secret is volatility.

The first thing to know is that smells are chemicals. All of them. Chemicals. Your nose has little chemical sensors called olfactory receptors and their function is to identify the chemicals that touch them, then communicating that information to the brain. But how do these chemicals get into the nose?

That’s where volatility comes in.

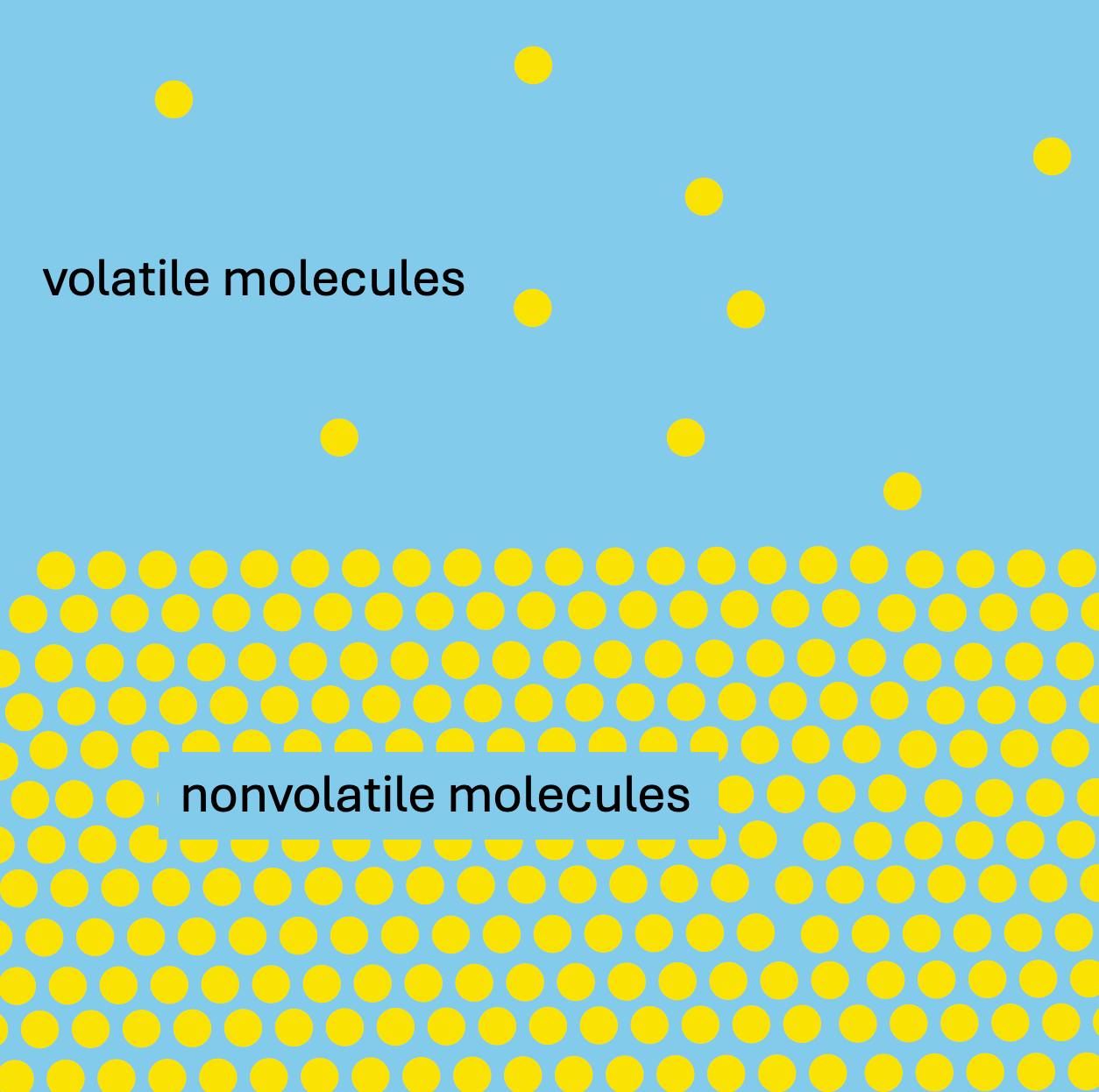

“Volatile” comes from the Latin root volare meaning “to fly”, which gives you a hint at its meaning. Molecules are “volatile” when they have become airborne. This is what smells are- they are molecules of a chemical that have somehow been coaxed into the air and can be carried to aroma receptors in the nose. If a chemical can’t become airborne, it can’t get into the nose and to those receptors. And if it can’t get to those olfactory receptors, it cannot be smelled.

But how do chemicals get into the air, anyway? One way is that they vaporize. That is, when they move from a solid or liquid to a gaseous state. And, though chemicals all vaporize at different temperatures, all chemicals vaporize more easily at higher temperatures. So, add a little heat, and chemicals get more volatile and jump into the air. And small, light molecules make this jump much more easily than large, heavy ones, especially if other chemicals are vaporizing around them. And this is why my facebook friend observed a different smell during the day: the warmth of the sun makes everything lighter and more volatile, all the oils in the plants and the gases in the soil and the dew on the grass. And all these things jump into the air and get carried to her nose. It’s like a levitation act, and it makes the day smell different than the night.

It's easy to forget that the things we smell are tiny particles carried upon the air. Smells seem like spirits- immaterial and invisible, more like ghosts than matter. It’s their lightness that makes them seem this way, and this causes all sorts of strange phenomena. One of my favorites is the case of acetic acid. Our common name for acetic acid is vinegar; tiny bacteria called acetobacter consume alcohol in wine and excrete acetic acid to make vinegar. Acetic acid is different from many other acids in that it is very, very volatile. Unlike, say, citric acid, acetic acid molecules form very weak bonds which make it possible for them to be swept up into the air easily. This is the reason that if you open a jar of vinegar or pickles you can smell it across the room in just a few seconds. Molecules of acetic acid have jumped into the air and made it to your nose that quick.

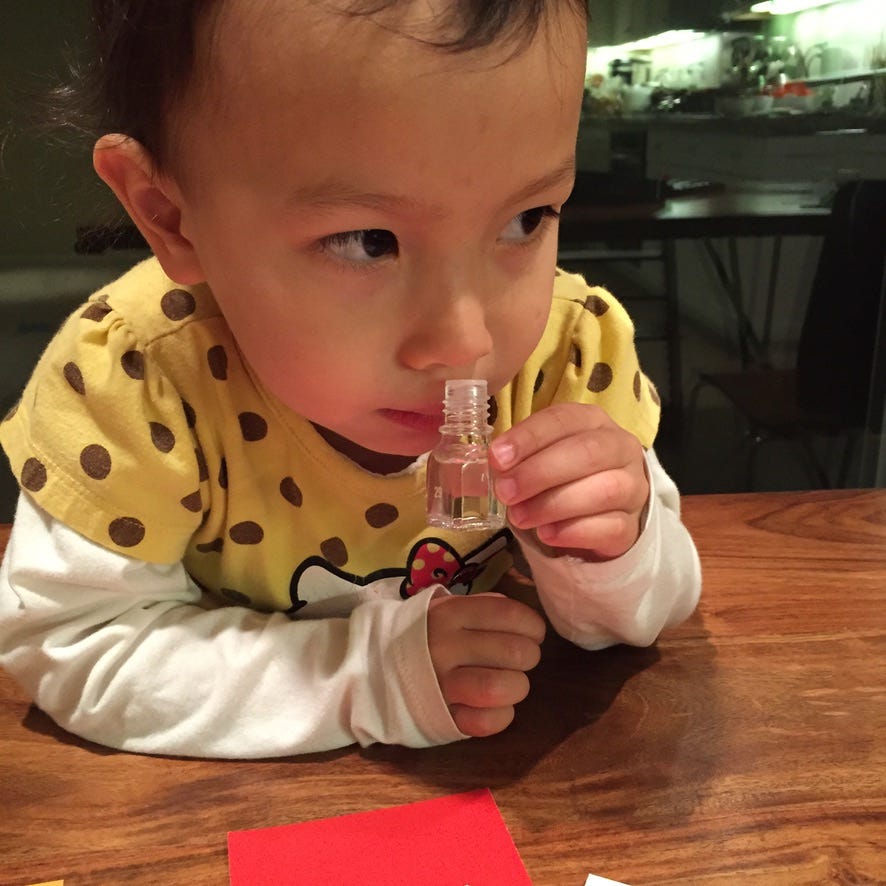

Volatility also explains another major feature of food: how aroma affects flavor. If you have a jellybean handy, or any fruit flavored candy, pop it in your mouth while holding your nose closed. Chances are, you’ll struggle to identify the flavor. But release your nose, and suddenly flavor appears. What gives? It’s clear that your sense of smell is somehow involved in the perception of flavor. But how do those volatile molecules get from your mouth to your nose, even if your mouth is closed? It turns out our nasal cavities have two openings: one in the front (your nose) and one in the rear (a passage called the nasopharynx). When you chew food, the agitation and warmth in your oral cavity liberates some aromatic molecules in the food, causing them to go airborne right in your mouth. If air is flowing through the nasopharynx (that is, if you haven’t plugged your nose or have a cold), it carries volatile chemicals to your nasal cavity via what amounts to a “back door” to your nose. Flavor scientists call this the retronasal (behind-nose) pathway. Retronasal aromas can come up from the throat too- as you swallow food or drink, the warmth of your body volatilizes some of the chemicals, sending them up to the nose retronasally.

The phenomenon of volatility is also one reason cooking food makes such a big difference. For one thing, heat volatilizes chemicals in the food, sending them into the air. So if you come home and smell pasta sauce on the stove, it’s because the heat of simmering has levitated sulphur compounds from the onions, aldehydes from the tomatoes, and terpenes from the basil which fill the air, waiting for your nose to inhale and identify them. But keep in mind: once these molecules have been volatilized out of the food, they don’t come back: this is one reason flavor changes as you cook- food loses aromatics steadily during the cooking process. Cooking too long or too hot can deaden the aromatics of a food- this is why fresh tomatoes smell floral and bright but long-simmered tomatoes do not. Finally, volatility explains why we prefer to eat hot food: it smells so much stronger. This applies both on the plate and the palate- hot food is much more aromatic than cold food in every possible way. It’s why warming a brandy snifter with the hand “liberates” the liquor’s fragrance, and why hot coffee is so appealing. It’s why you can breathe in a hot bowl of soup, an experience nearly as fulfilling as sipping it.

And it couldn’t happen if molecules couldn’t float on the air.

Aromatics! My favorite subject.

When I developed Essential Douglas Fir Shortbread for Essential Confection, I integrated fir essential oil into the Euro-style butter. Even flavors outside the food system have affinity relationships with other flavors so I included lemon essential oil as a boost. The butter has a killer mouth feel, and the flavors are grounded in galangal and pink peppercorns.

First learned about volatiles in wine country 20+ years ago. Volatilizing the esters!

My motto: Taste + Aromatics = Flavor.

I assume this is why food tastes and smells so different on an airplane? Different air pressure means different volatility?