When Candy Bars Were Health Food

Our grandparents lived in a world where Snickers bars were seen as healthy. I'm not kidding about this.

The other day, a Conan O’Brien podcast episode popped into my feed, in which Conan and his sidekicks spent the entire episode mocking the talent coordinator’s snack baskets. The joke was that the coordinator- a guileless young woman named Maddie- was stuffing the baskets with “healthy” snacks: roasted seaweed, crunchy Inca corn, and- the object of maximum derision- mushroom jerky. While Maddie defends her choices (“but celebrities like to stay in shape!”), Conan insists that what people really want is unhealthy snacks, like Doritos. Oddly, one of the “healthy” snacks in the basket is called “Rusty’s Island Style Hand Made Healthy Non-GMO Gluten Free Potato Chips” (never mind that they contain essentially the same ingredients as Lay’s). While they mock the chips, someone else munches on a “healthy” peanut butter cup. Clearly, the podcasters- and Maddie- have a clear sense of what the rules of “healthy snacks” are, and what “unhealthy” snacks look like.

The thing is, notions of “healthy” are not exactly consistent, at least not over time. My favorite example of this is… the candy bar. Candy bars are today considered the epitome of unhealthfulness, loaded as they are with sugar. But during the first half of the 20th century- the golden era of the candy bar- they were basically considered health food.

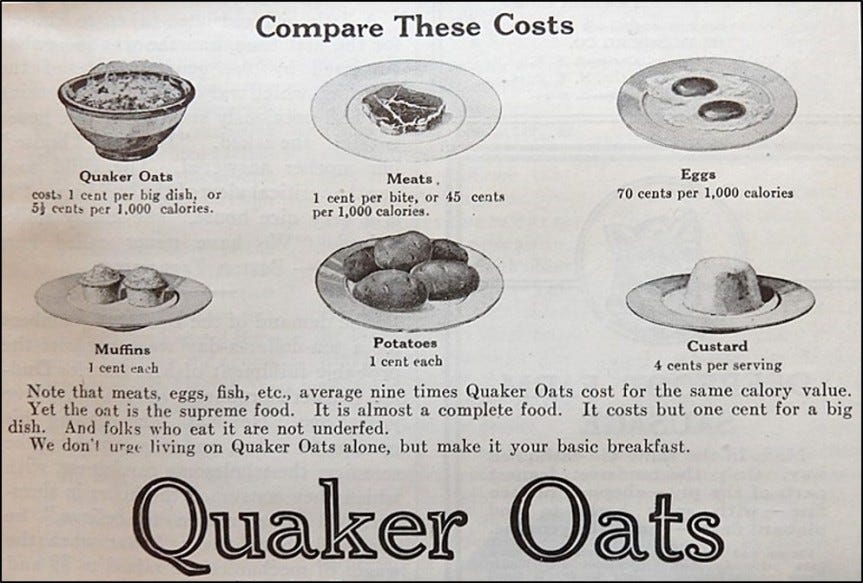

In order to understand this, you need to first understand the condition of the American food system in the early 1900s. In the days before synthetics, fertilizers were expensive, so food was, too. For the working classes, undernourishment- as in, a lack of sufficient calories in a day- was a real worry. Many food companies promoted high calorie counts as a positive attribute- calories equaled health and sustenance to many Americans.

The other major factor was food safety. As food systems grew- especially in urban environments- food contamination and adulteration became a big problem. In a time when milk was transported in unrefrigerated cans and flour was sold from open barrels in grocery stores, spoilage and infestation were the norm. Multiple scandals rocked the food industry- companies adding chalk to watered-down milk, grocers adding sawdust to coffee grounds, and questionable meats from filthy slaughterhouses. Consumers learned to exercise extreme suspicion of the foods they bought even as they tried to economize.

Enter the candy bar. Candy bars were first invented as an extension of a candy that already existed: the chocolate bonbon. However, a candy bar could be popped out of a mold instead of hand-dipped like traditional chocolate confections, and were therefore much less expensive. Handmade luxury chocolates were sold at counters, but candy bars were packaged- the candy bar could be wrapped and sealed at the factory, ensuring freshness and purity. Chocolate bars were perfect for selling at groceries or drug stores, not needing the special care of a confectioner. Soon, the candy market- then as now dominated by children- started to include adults who found the candy bar to be an enjoyable treat and a fortifying calorie boost. Soon, candy companies began marketing candy bars to adults, and emphasizing the caloric value of their bars. The idea was that a candy bar could be food.

One of the first to embrace this concept was the Klein Candy Company’s “Lunch Bar”, a peanut-chocolate bar that emphasized the quality of milk and peanuts the chocolate was made with. The Lunch Bar was introduced in 1913, and like Hershey’s, they grew their market by working with the US military to include chocolate bars in World War I rations. The bar was a huge hit, and was the most popular candy bar in its heyday. Soon, Frank Mars introduced the Milky Way bar, advertised as a healthy “double malted milk in a candy bar”. Another hit. But the candy industry was just getting started.

In 1923, Milwaukee’s Sperry Candy Company introduced the “Chicken Dinner” candy bar, a 5 cent bar that was said to pack the calories of a full chicken dinner into a single bar. The bar contained no chicken- just chocolate, peanuts, and condensed milk nougat- but the “wholesome and nourishing” tagline made it a big seller. Sperry launched a fleet of delivery trucks decorated as chickens, advertising the bars.

Soon, Tom’s Candy of Columbus, Georgia introduced their “Full Dinner” candy bar, another variation on the theme.

This wasn’t just a marketing gimmick- it was sincere: before people realized high sugar consumption was dangerous, it seemed like a game-changer: candy bars could be a portable, healthy, and enjoyable source of calories at work or play, when finding a regular meal was a challenge.

Keep in mind that this was long before the “obesity epidemic”. It was a time when low body weights were seen as a shame and a risk. The great depression made matters even worse, as the poor lacked even more access to calories. By the time World War II came around, about 12% of recruits were rejected because of malnutrition. Candy bars were seen as a potential health intervention to increase calorie intake and body weight.

After World War II, however, everyday Americans began to recognize the importance of vitamins, minerals, and fiber in the diet, which spelled the beginning of the end for candy as a health food. The concept of the “empty calorie” emerged, as people sought different kinds of snacks. Another generation of health bars- often fortified with vitamin and mineral supplements and based on granola or nuts- entered the scene. Sugar went out of fashion as a calorie source.

The Chicken Dinner was discontinued in 1963, and Sperry’s Lunch Bar ended its 57 year run in 1970.

And so, ended the era of the “healthy” candy bar.

But did the era of the healthy candy bar really end? The Tigers Milk Bar is basically a modified candy bar that has a bit more protein added. I remember getting halva bars at health food stores in the late 1970s with my dad, delicious and packed with sugar. And now we have Clif Bar.

This is the most fascinating piece I’ve read all week. Who knew? (I mean, obviously you, but I was utterly clueless.)