Maximalism and Minimalism in Cuisine and Coffee

A theory of how culinary trends evolve, including the current moment in coffee.

A friend was turning forty, and to celebrate her birthday a few of us made an exceptional splurge- we met in Paris and dined together at the Restaurant Guy Savoy: a well-known, elegant, creative restaurant just steps from the Arc de Triomphe. The meal was multi-course, and it was spectacular: from the soup- a puree of artichokes, chicken stock, parmesan, and black truffles- to the dessert, which came in a candy globe filled with a fragrant smoke, broken by the waiter to reveal a mélange of fruits, custards, creams, flowers, and spices within. The meal was memorable in its kaleidoscopic complexity. The next night, which happened to be a drizzly winter night in Paris, I wandered the streets with this same friend. In the early hours of the morning, we noticed a delicious smell in the air. Following the aroma, we discovered a small bakery which had begun baking pastries for the next day. They were just pulling the first chocolate croissants from the oven and offered to sell us a couple. We paid the 1 Euro each, and stood there in the rain, eating warm croissants, the molten chocolate interior burning our tongues. Though this happened more than a decade ago, I can remember the experience absolutely clearly. The late night pastry was in many ways the opposite of the previous night’s meal- simple and humble, compared to the elegant and complex experience of the night before. But it was no less memorable, and in some ways just as compelling. These were two extremes of culinary experience- the “maximalist” approach of Guy Savoy, and the “minimalist” moment of a simple croissant eaten in the street.

These two poles of culinary expression- the minimalist and the maximalist- are a useful way to think about the culinary arts. Here’s the idea- that we can value complexity or simplicity in a cuisine, but, as opposite extremes, these ideas pull against each other. Because of this tension, a given cuisine- here we define cuisine broadly as “style of cooking”- might tend to favor one approach or the other. Today, culinary trends oscillate between the two poles- sometimes favoring the minimalist approach, later celebrating the maximal.

Historically, these two culinary approaches come from the “high” and “low” social stratification of premodern cultures. As the ruling classes established themselves in Europe, Mesoamerica and Asia, they distinguished themselves from “ordinary” people by the way they spoke, the clothes they wore, and the food they ate. This is what we now call conspicuous consumption; the act of demonstrating one’s wealth and power through what one consumes. From a culinary perspective, examples of this approach included the various “court cuisines” that developed around centers of economic and political power. In China, succeeding imperial dynasties led to the creation of what is now known as the Imperial Chinese Cuisine, a breathtakingly complex style of cooking that emphasized diverse ingredients and sophisticated preparation styles. In Europe, the ruling classes developed court cuisines as well, most famously in France: in the 17th century, French cooking became the default “high” cuisine of the European ruling classes, leading to what we now know as “haute cuisine”. High cuisines emerged all over the world, and when they did, they shared a few traits in common- ingredients were valued for their diversity and expense: imported spices, out-of-season delicacies (a real treat in the days before freezers existed), and foods which required long, complicated preparation. The skill of the cook became a point of focus, as cooks became seen as artists, composing aesthetically beautiful dishes for the elite to appreciate. In China, some dishes still bear the names of the cooks who invented them, several hundreds of years later. In France, the “brigade” system of training and celebrating cooks developed, elevating the head cook to the status of “Chef”, complete with regalia, title, and a distinctive uniform. The tradition of maximalist high cuisine carried on into the modern era through the hotels and restaurants of the elite, with all its traditions of complicated recipes, complex flavors, sophisticated technique, aesthetic beauty, and expense.

Meanwhile, the “low” classes developed cuisines as well. Of course, the salient feature of historic lower classes was often poverty, which meant a necessarily simple, monotonous, seasonal diet based on grains and vegetables. One made a cuisine out of what was available: grain baked into bread or made into porridge, served with what vegetables were available or easily preserved. Spices were imported, expensive and therefore rare- flavor came from the ingredients themselves. Over time, particularly in places where agriculture was reliable and relatively stable, this tradition of simple foods developed into a cuisine based on agricultural realities: usually a large amount of grain foods such as wheat bread, boiled rice, or tortillas, served alongside smaller amounts of fresh or preserved vegetables, vegetable oils, and fish. The “Cucina Povera” (Poor Cuisine) of Italy is emblematic of this concept- a tradition based on simple dishes of bread and pasta garnished with vegetables, olive oil, and cheese or fish. Often, philosophers would idealize the humble life of the rural peasant, celebrating simple foods for their healthfulness, frugality, and a kind of spiritual connection with the land. This low cuisine was minimal by necessity- it was determined by what was grown locally, was seasonally available, and affordable.

As the advent of modern abundance and an emerging middle class began to de-emphasize the material reasons for the high-and-low divisions of cuisine, choices began to emerge. By the 20th century, transportation improvements had made spices so inexpensive they lost their association with the ultra-elite. Meat became available to almost everyone in wealthy societies, and modern industrial agriculture meant that more food was available even as fewer people were involved in producing it. By the end of the 20th century, people in many parts of the world were so wealthy that eating at restaurants frequently was a possibility, and the advent of leisure time meant that cooking could be a hobby as well as a means of sustenance. Simultaneously, the emergence of modern national identities, which called for distinct national cuisines, meant that people and cultures could choose between the minimalistic approach of the “low” cuisines, with their virtuous, healthy simplicity, or the maximalist approach of the “high” cuisines, with their artful, complex sophistication. Italian and Japanese national cuisines drew heavily from the minimalist school. A perfect example is sashimi, which presents a single ingredient- fresh fish- in an elegant, studied context of extreme simplicity. Other traditional Japanese foods- soba noodles served in a simple broth, salt-grilled fish (shioyaki), or rice balls wrapped in seaweed (onigiri), are beautiful examples of sophisticated minimalism in cookery. In Italy, minimalistic, seasonal, and regional foods make up the national culinary identity: the pizza Napolitana, for example, which emphasizes few ingredients (wheat flour, tomato, cheese, herbs, and oil) and rustic, wood-fired oven cooking, or spaghetti cacio e pepe, pasta with only cheese and pepper. Italian cuisine is largely based on bread and pasta, garnished with vegetables, oil, cheese, and perhaps a little meat or fish. Meanwhile, other emerging nations embraced maximalist cuisines: Chinese Imperial Cuisine evolved into an ethnic cooking style that emphasizes sophisticated cooking skills- high temperature wok cooking and meticulous knife technique- along with intense, flavorful, complex spices, sauces, and ingredients. The Peking Duck, suffused with five spice, steamed, roasted, coated with honey, roasted again, and served with delicate crepes and sweet fermented bean sauce is a great example. Chinese dumplings, handmade small bites of perfectly flavored minced meat and vegetables wrapped in dough and steamed before serving are maximalistic in their execution- xiao long bao contains a little bit of clear soup inside, an impressive culinary trick. Mexican cuisine is spectacular in its diversity of ingredients, cooking techniques, and spices- a dish like mole poblano contains a dizzying number of components: several kinds of chiles, fruits, nuts, seeds, chocolate, meat, Asian spices, herbs, corn, sugar, onions and tomatoes stewed together in a beautiful, silky, complex sauce. Modern French haute cuisine, with its sophisticated sauces and techniques, maintains its maximalist identity, even as rural French cuisines embrace simplicity. And this brings up an important point- this minimalist/maximalist framework does not seek to essentialize foods or cuisines as either minimalist or maximalist: indeed the emergence of what food historian Rachel Laudan calls the “middling” cuisines of the modern era means that people can emphasize either- or both- of these ideas in their food choices and ethics. A contemporary middle-class eater gets to construct a food philosophy based on aesthetics and preferences that pull in either direction. However, it’s useful to notice how food cultures embrace the tenets of either culinary minimalism or maximalism. And, because we tend to rationalize and moralize our cultural choices, it’s interesting to observe how these two poles manifest in food culture.

Modern culinary trends often point one way or the other, sometimes embracing the maximalist approach, other times embracing minimalism. From the 60s through the 80s, culinary maximalism was on-trend among elite foodies in the US: Julia Child and Jacques Pepin popularized French haute-cuisine technique, while Wolfgang Puck’s “fusion” style of California cuisine brought together global flavors in a creative and complex way. Puck famously created a restaurant that became a magnet for Hollywood celebrities- the modern American equivalent of royalty. A look at the New York Times’ restaurant page in the 1980s situates French haute cuisine and “Continental” restaurants at the top of the list. Culinary minimalism existed on the other end of the spectrum- especially among natural-food enthusiasts, who emphasized simple dishes of whole grains and vegetables for ethical or health reasons. The tables turned in the 1990s, however, as American elites embraced a new trend towards culinary minimalism: led by chefs like Alice Waters in Berkeley, the ethos of the “farm-to-table” movement began to rise. This trend built off the French rustic food tradition rather than haute cuisine, and incorporated the health-food ethos of the American baby-boom counterculture. The result was a shift towards the minimal: simple dishes of selected ingredients, lightly cooked, with an emphasis on “seasonality” and “freshness”. Emblematic of this shift was the rise of Whole Foods, which began as a health food store, but became a temple for the elite farm-to-table ethos. Concepts like “organic” and “whole” emphasized the purity of ingredients and the rural lifestyle, and products like “country loaves” of wholegrain bread evoked a rural, basic minimalism. The maximalist approach of haute cuisine began to be seen as unhealthy and overindulgent. Minimalist ethnic cuisines like Italian and Japanese had a home in this movement (Whole Foods had pizza and sushi stations) but the maximalist Mexican and Chinese cuisines generally were relegated to the less valued “ethnic” or “fast food” category. In Italy, the Slow Food movement became the standard bearer for the farm-to-table ideal, emphasizing an ethic of culinary rusticity, which sanctified the role of the farm and the farmer as the most important part of the food system. Maximalist traditions, like Persian and Korean cuisine, did not have much of a place in the farm to table movement, since their emphasis naturally skewed towards the craft of making complex foods and the skilled use of spices.

However, in the late 2010s, trends began to shift again, this time towards the maximal. Asian food traditions were a big part of this- the early success of Momofuku and Kogi put Chinese and Korean cuisines on the elite food radar- and the message was much more about the ethnic source culture than the farm. Today, Eater’s “Hottest Restaurants in LA” features several Korean and Mexican restaurants, others cooking the cuisines of the Levant and North Africa- all from the intensely-flavored, spice-forward maximalist tradition, with nary a mention of “farm-to-table”. We appear to be in a phase where culinary maximalism is again popular among the food elite.

What about Coffee?

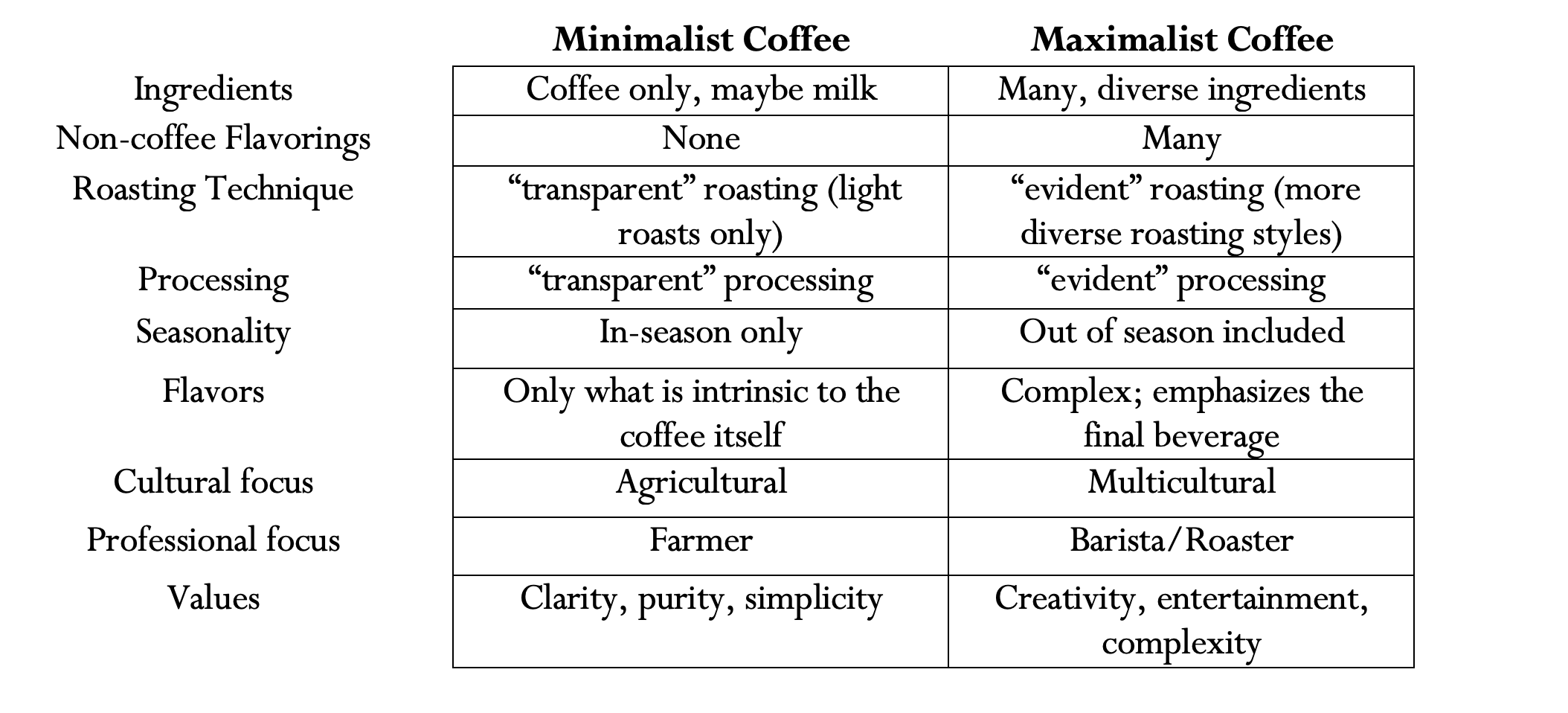

Coffee is, after all, a part of many larger culinary cultures and is profoundly influenced by them. What we now call the Specialty Coffee movement emerged in the maximalist-cuisine context of the 1960s, alongside the new enthusiasm for French cuisine and sophisticated restaurants. Alfred Peet, often considered a founder of the Specialty Coffee idea, played classical music in his shop, emphasized the role of the roaster in creating coffee quality, and looked to Europe for inspiration. But, the minimalist school wasn’t absent either- Peet’s shop was, after all, just a block away from Chez Panisse and, and Peet’s customers were, famously, among the long-haired counterculture (a movement that Alfred himself disliked). Peet was extremely focused on coffee as a singular ingredient, a minimalist trope. Speaking of which, how does the minimalist/maximalist cuisine duality apply to coffee? Here you go:

The first couple of decades of the specialty coffee movement leaned maximalist. Dark roasting was considered essential, inspired by the French and Italian coffee traditions. The roasting company was the focus, especially the coffee expert at the helm who crafted blends and roasts to create coffee flavors. Not to be outdone, the coffee bar got into the act, and in the 1980s the flavored latte was invented- espresso and milk laced with vanilla, nut, chocolate, or spice flavored syrups. However, a counter-movement was brewing. Many of the coffee companies staff began to resent the maximalist coffee approach- and eventually they began to found companies of their own. The fair trade movement put a spotlight on coffee farmers, and soon, the minimalist farm-to-table approach of Chez Panisse and Slow Food began to appeal to coffee people as a political as well as aesthetic choice. The “third wave” of coffee was decidedly minimalist- roasts became very light, coffee shops became austere in their design and menu, and people began to use phrases like “focus on the farmer”. The first two decades of the 2000s saw the rise of third-wave minimalist coffee, and many tastemakers began to see this approach as being synonymous with the idea of sustainability and fairness in coffee.

But it couldn’t last forever, and it didn’t. One element of coffee maximalism never quite left coffee, and that was the idea that the barista was an important and valuable culinary professional. Though many baristas developed the ideology and skill of celebrating the coffee farmer, the spotlight would generally be shared between the two professions. This was particularly evident in the growing popularity of barista competitions- where baristas would often discuss the coffee farm in passionate detail, but the memorable part was the signature beverage- a full-on demonstration of coffee maximalism. Meanwhile, specialty coffee became popular in Japan, Korea, Mexico, Brazil, and Indonesia- and each of these cultures began to contribute cultural “flavor” to the idea of specialty coffee, adding beverages and flavors to the coffee playbook. And, finally, coffee processors got into the act, themselves adding flavor to coffee through creative processing techniques, just as the baristas and roasters added flavor to coffee. By the 2020s, we had entered a period of coffee maximalism that paralleled the maximalism of the larger culinary world. Coffee shops, which during the third-wave era often had a minimalist uniformity, were instead celebrating diverse cultures, flavors and décor; featuring drinks like the horchata latte, and pushing the limits of coffee complexity and style. And, excitingly, the maximalists refused to cede the concept of sustainability to the minimalists: though minimalists suggested that simplicity and agricultural focus was essential to sustainability, maximalists point out that a broader, multicultural focus that celebrates multiple elements of the supply chain can be a path towards greater sustainability as well.

Where does that leave us? In my view, we’re solidly in a phase of both culinary and coffee maximalism, that is, a time that celebrates complexity over simplicity in food and coffee. The minimalist school is not gone- it’s just not ‘on trend’. For one thing, Instagram favors maximalism- a spectacular presentation is generally more photogenic than a simple one, and maximalism reflects the current younger generations’ enthusiasm for cultural diversity, vivid colors and flavors (see: the Barbie movie and Le Croix), and individual expression (from dietary restrictions to customized Starbucks orders). However, in the background, a new generation of minimalists are honing their crafts and their tastes, preparing for another surge of minimalistic, ingredient-focused cuisine and coffee.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moctezuma%27s_Table

This is the first post of yours I've found cause to generally disagree with. I don't think the premise makes much sense and the examples given don't generally support it.

Right at the outset you contrast an elaborate meal at Guy Savoy with a "simple" pan au chocolat, but anyone who's ever learned the art of making French pastry knows that there is nothing simple or minimalist about making a croissant of any sort.

Later on Alice Waters is cited as an exemplar of minimalist cuisine when in reality she's a well-trained French chef who. Yes, she's focused on ingredient quality and freshness like any other French chef but many of her dishes are quite elaborate - as I can attest from having cooked my way through her cookbooks. This is just one example on the cuisine front - I could cite several others.

The minimalist vs. maximalist schtick doesn't work any better with coffee. If we take Freed, Teller & Freed or Peet's or Schapira's - all among the oldest specialty roasters - as examples, all of them were extremely focused on showcasing origin flavors and disapproved of any additives to their coffees. Beverage service at all of these places was either nonexistent or extremely limited so that they could focus on selling coffee for folks to brew at home. The line out the door at Peet's on Vine Street was people lining up to get 8 oz. cups of drip coffee - and a tool to get customers to buy beans and brew them at home.

The supposedly minimalist Third Wave roasters mentioned are cited as being "transparent" in their roasting, but there's nothing murkier than grainy, underdeveloped coffee - especially if run through an espresso machine, whose amplification of acidity makes the shot taste like lemon juice. These folks simply wouldn't be in business if their customers actually had to taste what they're drinking, but fortunately the oat milk, panoply of flavorings and inherently bland (by reason of both manufacture and temperature) cold brew (not to mention free wi-fi) mask many sins of commission and omission. Oh and the "seasonality" thing is a total joke. In perhaps a hundred visits to such roaster-retailers I've never found a single one who sells only coffee from the current crop cycle.