There is a saying in Italian, something like “Be sure to eat a sweet breakfast, because life is bitter.” This is said to explain why Italians eat pastry, fruit, and even ice cream as the first meal of the day. But talk a little more to any Italian, and you’ll quickly learn that the bitterness of life- whether metaphorical or literal- is something to be embraced or even loved. Like grief, loss, and anger, the Italian attitude towards bitter is complex and passionate. Bitterness is something to be savored and explored, even if it can be unpleasant. Maybe it’s no coincidence that the Italian words for love and bitter- amore and amaro- are so similar. Love and bitterness, kisses and tears. Italy loves a contradiction.

Bitterness is, to me, the most interesting of the taste sensations. I call it “the taste of danger” because, evolutionarily speaking, it exists to warn us: bitterness is the sense we developed to keep us from eating poison. Though only one or two chemicals taste salty, thousands of compounds taste bitter to us: many many plants have evolved to accumulate toxic, bitter-tasting compounds to protect themselves from animal consumption. In turn, most animals- including humans- have developed an instinctive aversion to bitterness: a drop of sugar on a baby’s tongue elicits expressions of joy, but a drop of bitter makes a child grimace, gag, and cry.

But it’s not so simple. First of all, as they say, “the poison is in the dose”. That is, everything is toxic in large amounts and nothing is toxic in the tiniest amounts. And things that are toxic in large amounts can be healthy in small doses. So bitter can be healthy, or it can be toxic. Weird. Furthermore, ruminants- those animals who survive by eating leaves, grasses, and other plant material- would starve if they couldn’t tolerate the bitter compounds that plants create. So, many species have developed tolerance for plant toxins and bitter tastes alike. Pigs, for example, have evolved to eat acorns loaded with tannins, which are toxic and bitter to most animals. This isn’t only genetic- cows who graze on bitter weeds develop a higher bitter tolerance than grain-fed cattle. Carnivores, on the other hand, avoid bitterness like crazy: there is no good reason to ingest plant toxins if you survive on meat alone.

Omnivores like us are somewhere in the middle: we have the built-in bitter avoidance mechanism of the carnivore, but can learn to tolerate bitterness like a herbivore does. This creates a paradox- a love-hate relationship with the taste of danger. Since the very beginning, humans seem to have flirted with bitter tastes: archeological discoveries indicate that the earliest humans would add a few bitter seeds to gruel when cooking pulses, suggesting that even the first cooks were modifying the flavor of their food. And bitter isn’t all bad: some antioxidant compounds like polyphenols are both bitter and healthy.

As humans developed the art of cooking, we sometimes intentionally integrated bitter tastes into our diets. Those cuisines which are based on plants are, unsurprisingly, friendlier to bitterness than meat-based cuisines. And one of the most famous plant-based cuisines in the world is the Mediterranean diet of Italy.

Perhaps no cuisine in the world is more bitter-positive than the Italian cuisine. My mind instantly goes to the cured black olives beloved by my Sicilian grandparents: they look like oily raisins but they have the most powerful bitter taste imaginable. But it’s not just olives: Italians love bitter foods of all kinds and make bitter beverages to drink with them. One cannot eat Italian food without embracing and understanding bitterness- one might say that bitterness is to Italian cuisine what spiciness is to Mexican or Thai food.

Bitter and Green

My Sicilian nannu used to wander the vacant lots and fields near his home looking for wild mustard or dandelion greens to pick and bring home. My nanna would boil or sauté them, as an accompaniment to pasta or as a side dish. Italians love bitter greens in dozens of forms: sometimes referring to them generically as scarola. But it’s more than escarole- cimi di rapa or rapini, the broccoli relative prized for its bitter taste, is sauteed with sausage and served over oricchette pasta. Radicchio is a powerfully bitter vegetable, eaten in salads. In fact, a visiting American will instantly notice that even lettuce is more bitter in Italy than in the States- Italians favor bitter-tasting varieties while Americans love the crunchy, watery kind. Ciccorino, rucola, and broccoletti… the list of bitter vegetables goes on and on, added to soups, sauteed and served on bruschetta or pasta, or used as a pizza topping.

Drinking Bitter, appetizing and digesting

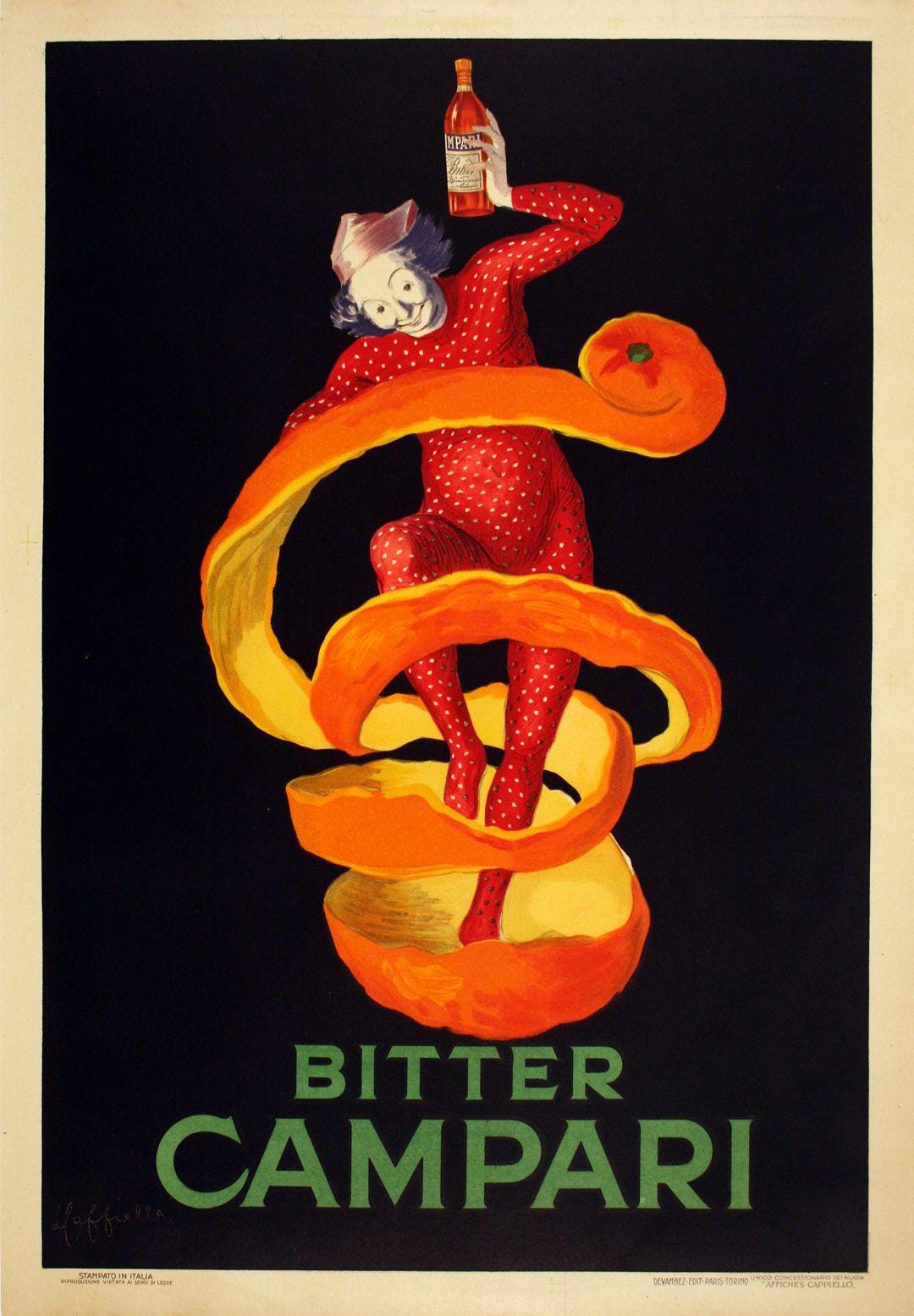

The ancient Greeks and Romans both believed that bitter herbs aided digestion, a concept they may have picked up from the ancient Egyptians. Certainly it was the Egyptians who began mixing wine with medicinal herbs; archeological evidence shows evidence of the practice as early as 3000 BC. Today, Italians drink a huge number of alcoholic bitter herbal concoctions called amari or “bitters”- the rationale is digestive but the Italians seem to do it for enjoyment. Bitter liqueurs consumed before eating are called aperitivi, and they include the famous Campari and Aperol: drunk with soda water or in a wine spritzer, they provide a cooling, stimulating way to start a meal. After the meal, a different type of amaro is drunk: liqueurs known as digestivi. These tend to be dark, complex, and very very bitter: Fernet-Branca, Cynar, and Averna are three examples of the style. These liqueurs get their bitterness from botanicals like gentian, chinchona bark, citrus peels, and hundreds of other herbs. These drinks are a motherlode of bitterness, and are consumed every day by millions of Italians.

Bitter Coffee

Of course, coffee is one of the most familiar bitter drinks in the world, and Italians can’t be without their daily caffe. Italians- particularly in the South- embrace the bitter aspect of coffee more than almost anyone else, favoring roasting styles, coffee types, and preparation styles that maximize bitterness. This bitterness is generally balanced by copious use of sugar: such is the way of things in Italy. Not all Italian coffee is bitter-centric, but a lot of it is, and Italians know how to balance and modify bitterness in coffee better than anyone. (Naturally, I will take a deep dive into coffee bitterness in a separate Pax Coffea post).

Want an Italian recipe that embraces bitterness? Here’s one:

Senape con olive e formaggio (mustard greens with olives and cheese)

Wild mustard grows everywhere in Southern Italy and Sicily, and is a descendant of the “wild cabbage” that is the ancestor to the cruciferous vegetables. Sicilians love bitter greens, and my Sicilian-American grandfather would sometimes return home from a walk with an armful of mustard greens he had discovered growing in an abandoned lot or roadside. Sauteed with olive oil and garlic, and flavored with olives and salty cheese, this dish is a fantastic tribute to bitterness in vegetables.

1 large bunch mustard greens (you may substitute cimi di rape, kale, collard greens, escarole, or any bitter dark green leafy vegetable)

2 cloves garlic, finely chopped

Approx. 1 cup black olives (kalamatas are great for this, but if you really want a hit of bitterness try Italian oil-cured olives)

3 tbsp. good olive oil

grated Pecorino Romano

Heat a saucepan of salted water as if you are going to make pasta. Once boiling, add the mustard greens to the water and cook 3-4 minutes. Remove from the water and drain.

Heat the oil in a sauté pan, and when hot add the cooked greens and garlic. Sauté for a few minutes. Before the garlic browns, add the olives and toss. Season with salt and pepper, and transfer to a serving dish, sprinkling liberally with Pecorino Romano. Serve as a side vegetable with chicken, pasta, or on toasted bruschetta.

This is the digestif I was telling you about: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chartreuse_(liqueur)

Past participle of “to love” (“loved”): “amato”. First person of the future tense (“I will love”): “amerò” - even closer to “amaro” ☺️